The great majority of the local inhabitants are farmers, although the region also contains numerous groups of pastoralists, who periodically move with their herds of zebu cattle in advance of the drought. The herds of cattle owned by pastoralists are a source of milk and milk products that are exchanged with farmers for their crops - the basic crop in the region is millet, particularly that variety known as sorghum. The local menu is complemented, of course, by hunting and fishing.

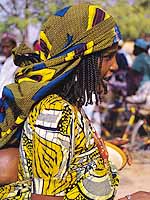

The Mandara highlands and their immediate surroundings are home to a broad range of ethnic groups, who in the main can be classified as belonging to the Chadic group of the Afro-Asian language family. These ethnic groups have accepted neither Islam nor Christianity, and remain faithful to the traditional cults of their ancestors. Each group speaks its own language; those individuals participating in inter-ethnic communication speak a second language, today predominantly Fulbe. These people all lived until recently in relatively closed communities, and their mutual contacts were strengthened until the administration of the European colonial powers, who wished to draw these wild montagnards into a money-based economy, in order that they could pay taxes. For this reason, the growing of ground nuts and cotton - known in the Mandaras earlier, but grown only to a limited extent to meet family needs - was encouraged; it was the Europeans who first turned their production into a trade.

A glimpse of the life cycle and traditions of the inhabitants of the Mandaras is afforded by ethnography. Thanks to many years of study, and a series of ethnographers who have lived among the local peoples, extremely valuable studies of individual aspects of life in the Mandara highlands are now available. The space available to any single publication precludes the presentation and comparison of large numbers of examples, and nor has that been the aim here. The authors have concentrated on the southern Fali populations, while in several cases also giving examples from the life cycle and traditions of the Mafa of the north. Among both groups a particularly special place is held by smiths, who in addition to their dark craft bury the dead and arrange funeral rites. They form a specific group of their own, sharply divided from their given ethnos. Smiths' wives are midwives, and among several ethnic groups it is also they who make ceramic wares for their whole villages. Smiths are bound by tradition to marry among themselves, in a system of caste endogamy.

Ultimately, even among the typical, non-smith population, certain rules regarding the selection of a marriage partner are valid even today. Young men seek their partners outside their own clan - a system of clan-based exogamy - and generally settle in the village from which they come. The clan must be understood rather as a religious unit than as a kinship-based one. Orphans are customarily adopted by one clan or another, and their original clan designation is then forgotten. The clans themselves cut across entire ethnic groups, where they thus often become a dominant social element. Clans or ethnic groups can be distinguished on the basis of certain cultural attributes, and in particular by the conduct of given rituals and ancestor cults, but never - as made clear above - on the basis of biological characteristics.

A glimpse of the history of the inhabitants of the Mandara highlands is provided by archaeology. The settlement of the broader area around Lake Chad is linked to the beginnings of agriculture, documented on a whole range of carvings and paintings in the rocky massifs of the central Sahara. This was a time when it still rained in the Sahara, and when Lake Chad itself reached almost to the Tibesti. Its shallow expanse, however, soon shrank, and from the 8th century AD the first states began to appear around, linked to the slave trade. This trade reached an unprecedented level during the rise of the Bornu empire which appeared west of Lake Chad, and the expansion of its power and territory can be well followed in the archaeological finds from sites along the southern edge of the lake.

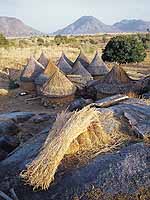

The society which in the early 15th century came into conflict with the expansionist Bornu empire is known as the Sao. The bearers of this culture created remarkable ceramic sculptures of great artistic value. Over time, however, this culture collapsed as people accepted Islam or fled before the plundering raids of the Bornu slavers from the west. They had little alternative - to the east their path as blocked by the Baguirmi empire, while to the north the many islands in Lake Chad were already settled - the northern Mandara highlands thus immediately presented themselves as a suitable refuge from several points of view. Here dwelt demographically less numerous groups, among whom it was easy to penetrate. As in the lowlands or along the rivers Logone and Shari, in the mountains it was possible to find a form of agriculture suited to the terrain - the available land surface could be expanded by the building of terraced fields. The availability of even overproduction of foodstuffs, and the threat of Muslim incursions, led to an increase in the birth rate, as was identified even by demographic surveys carried out in the 1960's. Among the populations of the southern Mandaras and the area north of Garoua, however, this tendency was not preserved.

The interpretation of the present situation, which is characterised by the highly diverse ethnic composition of the inhabitants of this part of Africa, is a purely anthropological issue. The ethnographic and archaeological facts described provide a conceptual framework allowing an assessment of the causes of the biological and genetic diversity of the region. The authors believe that in this part of the world individual socio-historical events have in some way been inscribed into the genome of the modern population. Population in the biological sense of the word must be understood in the wider context of these events, particularly when one sees how strongly ethnicity or ethnic identity is subject to both power-political and social pressures. In this book, the authors have attempted to provide a popular synthesis of the study of Man; the reader will judge to what extent their somewhat Gauguinesque sketches have been successful in showing from whence these people come, who they are, and where they are heading.