Specialist: RNDr. Miriam Nývltová Fišáková, Ph.D.

For some decades now, scientific methods have provided general help in analysing artefacts, ecofacts and find situations. Within the Czech Academy of Sciences Institute of Archaeology methods based on the fields of geology, geochemistry, biology and chemistry in particular are applied in a specialist facility. Using selected methods, such as analysis of the proportion of stable and radiogenic isotopes, analysis of the growth of dental cementum and palaeogenetic or multi-element analysis, one can determine much about the origin, migrations, diet, hunting and economic strategies and physical condition of the population under study.

The group of basic methods applied over the long term includes zooarchaeological and palaeontological analyses which describe the skeletal remains of animals discovered during archaeological digs, and in particular their elementary anatomical identification and allocation to species. As an example, a set of fauna skeletons from the early Palaeolithic site at Přerov-Předmostí have been assessed. This provided a classic sample of representatives of cryophilic fauna, a mammoth, cave bear, wolf, auroch and reindeer. Zooarchaeology also complements research into later human cultures. One example might be the oldest demonstrated recording of a greyhound on Czech Republic territory, the skeletal remains of which come from the Slav settlement of Chotěbuz-Podobora. During the 2005 dig season two canine radius bones were identified in accumulated osteological material. Using comparative osteometric analysis and analysis of mitochondrial DNA it was shown that this was a greyhound. Analysis of the stable and radiogenic isotopes (Sr, C, O, N) from the greyhound radial bones showed that the greyhound had been brought to the settlement from a coastal area, probably from the Baltic. This greyhound evidently arrived in the settlement from the north as a gift, plunder or as a rare trade item from this region.

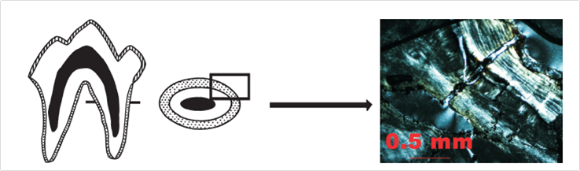

A further scientific method is the analysis of incremental dental cementum. Dental cementum is laid down through the whole life of an individual with varying degrees of intensity in summer and winter months, rather like annular rings in trees (Fig. 3). The reason for this is the varying activity of the cementoblasts which is affected by the relative percentage of mineral and organic composition. One can therefore track not only the age of an individual, but also determine the season in which death occurred (the activity of the cementoblasts, and therefore the growth of the cementum, being prematurely terminated, Fig. 4). Thanks to the study of the teeth of large mammals discovered in Gravettian Palaeolithic sites it has been confirmed that these animals were also hunted in the winter months and that these large settlement areas in the Czech lands (e.g. the Dolní Věstonice – Pavlov, Přerov – Předmostí sites and others) were occupied all the year round, in contrast to small seasonal sites (e.g. Boršice, Jarošov and Spytihněv).

Other methods used at the facility include analyses of the proportions of the isotopes of strontium, oxygen, nitrogen, carbon and sulphur (87Sr/86Sr, 18O/16O, 15N/14N, 13C/12C and 34S/32S) in the bones of both animals and humans, through which the life-time diet and migrations of these individuals can be established. Strontium isotopes get into the biosphere and into the food chain through the erosion of crystalline volcanic rocks and their highest concentration is to be found in plants which take them in in water through their root system. Through the proportion of isotopes we can therefore track the diet of humans and animals, strontium in the biosphere in relation to the composition of the geological bedrock. Specific analyses of the proportion of strontium isotopes were used to study the migrations of Palaeolithic fauna. They showed that horses migrated medium to large distances, of the order of hundreds of kilometres and not thousands, as previously believed. Similarly the hypothesis of reindeer migration during the high Gravettian period was overturned, whereby this was more a local vertical transfer from the lowlands into the mountains (greater territorial shifts taking place in connection with climate changes during the late Gravettian). In mammoths great migrations were shown in a north-south direction during the high Gravettian, with east-west migration (along the Danube) during the late Gravettian (Willendorf-Kostenkov phase).

A further method which offers wide scope for interpretation is the analysis of burnt skeletal remains. A unique position was again uncovered at the Chotěbuz-Podobora site during the 2009 dig season. This was a building with burnt animals "in situ". The remains were found of three sheep, a dog, a pig and a gravid cow (Fig. 4). Using infrared spectrometry (analysis conducted in conjunction with Ing. Luboš Prokeš from the Institute of Chemistry of the Natural Sciences Faculty at Masaryk University, Brno) the exact combustion temperature was determined, the intensity of which is variable in line with the type of tissue being burned (e.g. a high level of body fat facilitates burning, and for this reason the remains of the pig were the most consumed). This find of a burnt "stable" is a unique taphonomic phenomenon. At the same time, the circumstances around the find are witness to the dramatic results of what was probably a military attack on the site at the end of the 9th or the very start of the 10th century.

A new international project with good prospects is the research into the Stajnia cave in Poland, shared by the Uniwersytet Szczecin and the Dionýza Štúra State Geological Institute in Bratislava in addition to the Brno Institute of Archaeology. This is a unique set of remains of Neanderthals, the first found north of the Carpathians.

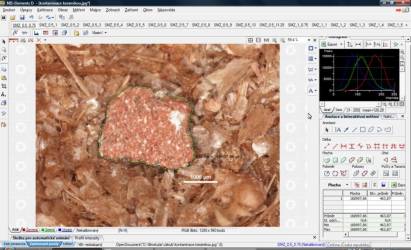

The scientific laboratory facility within the Czech Academy of Sciences Institute of Archaeology is equipped with the appropriate technology for taking samples, making specialist reports and final assessments. The specialised equipment includes a stereomicroscope and polarising microscope with CCD camera and high resolution, the outputs from which are processed using NIS-elements software which analyses the image.