“We had the opportunity to invest time into interdisciplinary research, knowing that if everything works according to plan, we‘ll rank among the best. But an overarching element of our research remains to be optics – we’ve never run away from it,” says Alexandr Dejneka, the Optics Division Head, in an interview. He took charge of the Division 15 years ago and has been developing it since then – not only towards the interdisciplinary research, a frequently discussed approach in science today, but also towards extensive collaboration with industry as part of the NCK MATCA and Brain4Industry projects.

When did you start recreating the Optics Division into an interdisciplinary Division with outreach to industry?

It’s been about 15 years since I took over the management of the Division. Shortly before that I’d been leading Department 21, which was originally focused mainly on applied optics, but its research programme was rather underdeveloped. So, to improve it, I first focused on research directions for which we had an expertise – optical spectroscopy and elipsometry. I managed to roll them out quite well, establishing some successful international cooperation projects too. The aforementioned elipsometry has been my personal focus – I defended my PhD thesis on it in 2002. At the Department we had the technologies necessary to do elipsometry, so I seized the opportunity and started developing the technologies available there. But as elipsometry was only a sub-direction, which was strongly linked to me, I could only assign it to one group, not to the entire Department.

However you very likely wanted to develop the whole Department – this must have been quite a challenge, right? That’s when you started considering going interdisciplinary?

Just then I started considering any other interesting directions that we might focus on. I attended a couple of conferences dealing with interdisciplinary research to get a grip on the demand in other research disciplines to see if we were able to satisfy it. Interdisciplinary research was beginning to be discussed aloud as a way of pushing science forward; until then research was usually focused on a single area: physicists did physics, biologists did biology, doctors treated patients, etc. But it was about then that the entire science world was starting to understand that physicists might be helpful to biologists and vice versa, so with this in mind, we started to penetrate deeper into the biological science territory – biology, biophysics, chemistry...

How was the first “dating” of physics and biology?

The problem was the two groups didn’t speak the same language. Also their approach to data analysis was completely different. So I did my best to be able to figure out the differences, and I gradually started to understand that our work in low-temperature plasma and material science, thin layers or optics as such show promise in terms of their application in interdisciplinary research. At that time, I was taking part in a cooperation project involving the J. Heyrovsky Institute of Physical Chemistry focused on the exploration of the phospholipid layer creation in liquids. As for physics, I was able to set up everything all right – we had interesting results, we were able to publish them properly, but in terms of my understanding of what’s going on there exactly....well, you see – before the project, I only had a vague idea of what lipids actually are. I had to study everything about them from scratch, and learn basic chapters from biophysics, chemistry etc. At that time, we started to collaborate closely with Dr. Zablotskyy, who works at our Division at the moment. He was interested in interdisciplinary research, in exploring the effects of electromagnetic field on things, including living objects and living nature.

So, the two of you started working together?

Yes, this cooperation was part of a complex puzzle consisting of any future collaboration opportunities and their application; we were discussing everything in a friendly and responsive manner, but we were just talking our visions rather than any concrete steps. We had no plan, we were only brainstorming ideas. We both had our own opinions, and neither of us wanted to step back, which is a relatively normal thing to do among scientist. Eventually, we came up with an idea to call on an institution that would be interested in applying physical methods and electromagnetic field in medicine. Or one interested in trying to do joint experiments with us. As a result, we invited the director of the Institute of Experimental Medicine for a visit. She supported our efforts, and we agreed on the first set of experiments. She delegated Dr. Kubin to try working with us – and this is something I am extremely grateful for because the delegated researcher Šárka Kubinová was a great partner, she studied hard the entire year, teaching us a lot about what she had learned. Anyway – it took us a year to start speaking the same language.

So you studied chapters from medicine and biology, and she studied physics, right?

Yes – so we’d be able to connect our ideas. As until then, we’d use the same words but they….

…referred to slightly different things? So how did you get on the same page?

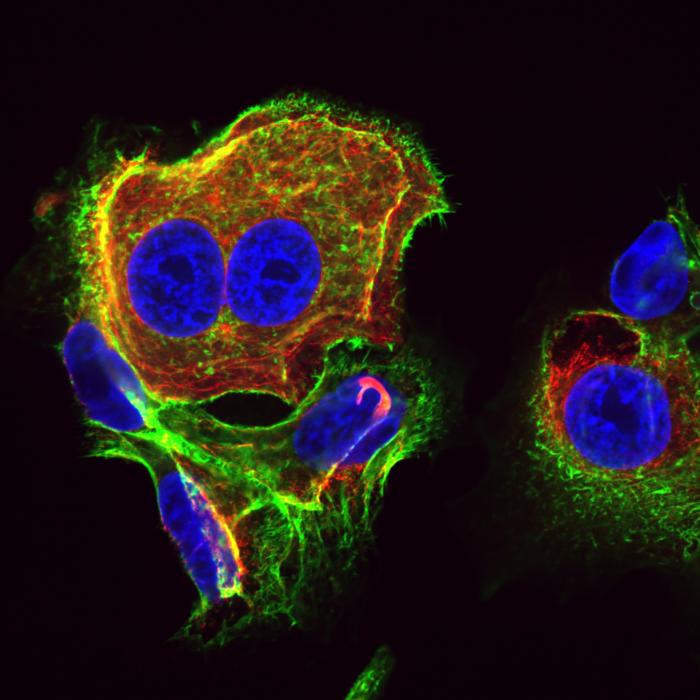

We’d meet regularly – we’d always pick up a topic and began to study it from the point of view of biology, and then of physics. We started exploring the development of low-temperature plasma and its impact on cells. We realized it could be used in the wound healing process. We had to study the complete vocabulary in relation to wounds, cell death and other cell phenomena. So for us, this was a crash course on medicine and biology. The same applied to Šárka, she studied chapters from physics – what is the definition of the charge, what does plasma consist of, how it works in terms of physics, etc. We were both doing our best, and it paid in the end. I think it, indeed, took us a year to fully understand each other. Throughout the year, we were already doing some experiments together, so it didn’t take us so long to start the real experiment phase.

Did you lead the Department or did you already lead the entire Division?

Both, I was already in charge of the entire Division for about a year at that time. During those six months I managed to stage a revolution of its kind at the Department, in terms of what the Department’s next steps will be. And this might be one of the reasons why I was invited to lead the entire Division too.

…and you’ve remained the Division Head until today. But let’s get back to the development of interdisciplinary research – we left off with your collaboration with the Institute of Experimental Medicine, but how did the new interdisciplinary groups come into existence directly at the Optics Division?

Another very important milestone was the collaboration with the Institute of Pharmacology in Ulm, Germany – the previous workplace of Oleg Lunov who joined us later. We started working together with a professor who led a team that Oleg Lunov was a part of, and we did a series of quite interesting experiments, which also pushed our work forward. So we basically had two very strong collaborations taking up at least 50 % of the engaged researchers’ time. A few years after we first conceived the idea of interdisciplinary research, a half of the Department was already exploring this direction.

How did your colleagues and, in fact, the management of the Institute empathise with the fact that the Optics Division had started dealing with bio-disciplines?

It should be noted that all the other disciplines have greatly benefited from the knowledge of optics – so even if we are talking interdisciplinary research here, optics has always been a dominant element for us – we’ve never run away from it – we simply had the opportunity to invest time into the development of interdisciplinary research to see if it works or not, knowing that if we succeeded, we’d rank among the best. But nothing could be planned ahead, because the fairly mixed research directions were only beginning to emerge. Also, it was clear that modern medicine can’t do without interdisciplinary research. All in all, physical methods laid the foundation of modern medicine – brain tomography, X-rays – none of these would exist without physics.

How was the collaboration with researchers from Ulm? What inspired you about this cooperation?

At one point, we made a huge leap forward together. In our team, we had Šárka Kubinová, a doctor of medicine, an expert on spinal damage and wounds, and they had Oleg, still based in Ulm, with expertise in biology, cell biology and biophysics. We were trying to figure out how to develop our research direction in terms of the overall management and higher efficiency. It was clear that the responsibility for this direction needed to lie with someone with in-depth knowledge of the field, and this wasn’t me. And, as the professor who led the team Oleg was a member of, was about to retire, we approached him to agree on Oleg’s joining us. And, as Ulm seemed very interested in a continued cooperation with us, they agreed. Oleg, in turn, was very interested in this direction as a whole; in the equipment available at the FZU, as well as in joining the FZU in terms of his career growth – in Germany he had a minimum chance of becoming the head of his own research group. In order to engage him in our research, we prepared a project and received funding from the J.E. Purkyně Fellowship. As a result, another group – a very tiny one at the outset – was created, which has been working smoothly now.

Well, this almost looks like a puzzle which solved itself.... you needed a research lead for a bio direction, and Oleg’s professor was just about to retire....

Well, we were actively involved in this, we were developing a number of collaborations simultaneously, and this one with Ulm went smoother than we imagined it at the beginning. And what’s more, the word of our developing bio-disciplines got around Czechia quite quickly. Also, this is how Hanka Lísalová’s research group was established 3 years ago. There was no such group before she joined us. She came together with her student Ivana Víšová – attracted by the capacities and equipment available bio-disciplines at the FZU. Neither of them is a biologist, they focus on material surfaces, biochips – but it’s about biochips targeting bio-molecules. They started employing the bio-team expertise quite quickly. To extend your metaphor, I’d say that Hanka’s arrival was the last missing piece of the puzzle as far as the Department’s overall operation is concerned.

And the puzzle is complete…

We had capacities for the exploration of physical materials; an expert technology team capable of manufacturing almost anything, and a Marina Tjunina’s team concerned with technology and with research of advanced materials, primarily of thin layers. Having all this enables us to propose, manufacture and explore materials for a wide range of applications, ranging from scientific, a very basic research, to industrial application. In Oleg’s research group, as part of the biophysical direction, we focused a lot on interaction of physical systems such as nanoparticles, magnetic and electric fields, low-temperature plasma, light, and light-cell interaction. And Hanka’s biosensor team was the required link between the two groups. She can make use of the two groups and link them via her sensors, because that’s where both surfaces and biointeractions are used. That’s the last piece to complete the puzzle as everything interacts with everything, and everybody can use everybody else’s knowledge.

And here we have it – the multidisciplinary Optics Division, it has flourished into what it’s today. When and why did Optics began to seek industrial cooperation?

Industrial application and cooperation were actively sought after already by the predecessor of my predecessor in the Division position. He was actively promoting an idea that the Czech scientist should not only get an opportunity to come up with an idea but also an opportunity to implement it in practice. This was when doing science was equal to doing basic research. I adopted this idea. Already as I was the Department’s Head, I would be approached by industrial companies now and then, saying that they know what we’re working on here, and asking us to manufacture a special product for them. Their orders were mostly rather simple and didn’t bring much money; on the other hand any reasonable income was welcome, and, moreover, processing the orders was also interesting from a scientific point of view. Frequently, they just wanted to test something that couldn’t be tested in their production environment. Such tests didn’t involve making products as such, instead it involved material testing etc.

However, there still was a long way to go to where we are today, right?

Yes, at that time it was. But in 2016, a company called CARDAM was established, which largely involved the Optics Division. We quickly managed to map out what we might offer to industry, and we found out there was a lot to offer. Even before CARDAM was created, I was involved in a few TAČR-type projects (Czech Technology Agency) or Ministry of Industry projects, whose output was to cooperate with industry, to manufacture industrial products or to provide industrial innovation. Within the projects, we provided a proof of concept to be taken over / completed by an industrial company. Now that there is CARDAM, we can benefit from it by directly offering solutions that are completely tested and proven. The solutions can then be further developed by an industrial company, or we can follow them through together with the company.

Then, in 2018, the MATCA National Competence Centre focused on applied research was established.

Yes. And, in the middle of it all, a call for proposals was announced by TAČR (Czech Technology Agency) to establish national competence centres. After consulting our partners, we realized that we already have all we need to establish a centre like that: we’ve identified the opportunities; formulated a clear idea of what we can offer; and ensured great capacities... It indeed might look like somebody was listening to us, and tailor-made the call for us. Therefore, we couldn’t say no to this, although the deadline was deadly; a lot of contracts were to be drawn up, a lot of partners to be addressed, a lot of signatures to be attached; it wasn’t easy at all to make it all happen – it was a struggle, but we did it! The first year of roll-outs that followed was rather hard too. We were familiar with the applied research projects, with the project formalities, the project dossier, but the centre’s existence was about something else.

What was the hardest thing about launching the Centre? What were the initial setbacks?

Not only did we have to solve the projects, but we also had to reorganize the other participants completely. The hardest nut to crack was to coordinate the cooperation between industrial partners and academia which had no experience with industry at all. It was again like translating a conversation between two people who speak a totally different language. But we managed to overcome these problems too, we followed the work through, we trained people. It goes without saying that there were setbacks, but we managed to overcome them to our great satisfaction. CARDAM and NCC MATCA have created a reliable platform for cooperation with industry that has actively been developed recently.

So your record includes the cooperation with CARDAM; the NCC MATCA is running well....Where did the idea of Brain4Industry come from?

Quite frankly, I’m unable to say exactly who came up with this idea. But the truth is that ever since the first CARDAM director, we and our technology partners have always dreamt of having our own testbed. This was because CARDAM was primarily established to provide design, computational and software capabilities. They don’t have any workshops or production facilities. However, as the company was beginning to develop very quickly, it was clear that having a testbed or that sort of thing might considerably push us and all our partners forward. We’ve been discussing this for a year or two, thinking it’d be nice to do something. We were considering a lot of options, including building a lab or even a small separate building. But we had no money for that. And, all of a sudden, we found out that Ministry of Industry announced a called “Applications”, but we found out rather late, and there was little chance of success for us. Eventually, we decided to take part in it, anyway, and we managed to win a subsidy as part of the call. At the start, the collaboration with industry was very hard. However, when we prepared the projects, we began to see that we are starting to understand each other. Industry has its clear rules, and you must, above all, do what you promised to do – there is no way around it. Once I promise to do something by a deadline, there’s no way I can fail to do so. I can’t talk your way out of it. Once you fail to keep your promise, you’re no longer a partner.

Is this the major drawback with the cooperation of academia and industry?

Yes, one of the major ones, in my opinion. I’m going to give you a concrete example. We were working on the development of an interesting instrument, and one of my colleagues, who was in charge of the development, didn’t want to hand the instrument over to the partners yet, as he felt he might still improve it. The instrument worked are required by the partners, but the colleague was convinced that the efficiency of the instrument might still be improved twofold and the cost efficiency fourfold – i.e. improvements that they must appreciate. He asked them for an additional month to deliver the results. Surprisingly, the partners agreed to wait for it, but told him they were pressed for time. In a month’s time, the colleague produced the results he promised, but he came up with another idea that would produce even better results if he changes the technology used. But the problem was I had to stop him. We delivered everything as required by the partners, even with some perks, and the partner was happy. However, the problem was – we are a research institute, where the underlying principle is making progress. Therefore, forcing a researcher to stop pushing the boundaries is going against the grain. Every great researcher gets easily frustrated by this. And you risk that you discourage him/her from doing their best.

What’s the most interesting result which has originated from the cooperation with industry so far?

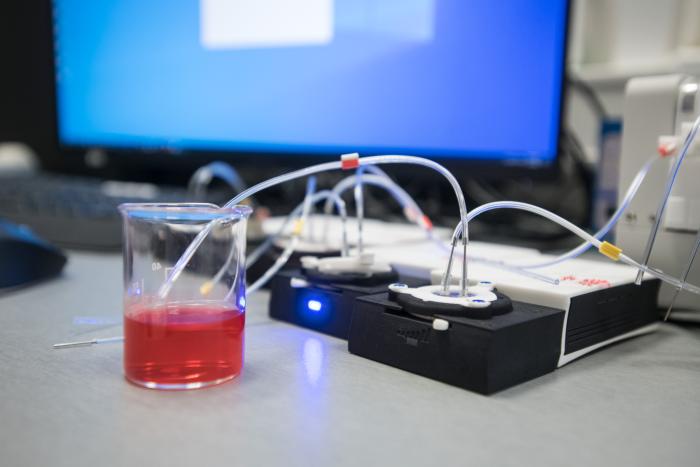

One of the most interesting projects which we followed through and can talk about publicly is, without a doubt, the low-temperature plasma generator to promote wound healing. It has been completely certified for use with animals – in veterinary medicine. The company that produces it is now planning a market launch. However, the ambition is even greater, because the technology turned out to work with humans as well. Recently, the Institute of Experimental Medicine has started a collaboration project with us to use our instruments in a clinical study to be conducted in a Burn Centre at a hospital in Brno, Czech Republic. That’s where its efficiency will be tested. We’re sure it’s going to work, but we need experimental evidence. We have a multiple page document with a list of all animals that have been healed using this method. The animals include dogs or horses. They have shown resistance to antibiotics, therefore complex wounds are healed using our instrument. One of the reported cases involved a dog attacked by a wild boar in the forest; the dog ended up with multiple life-threatening wounds. According to the vet surgeons, the dog wouldn’t survive and would be put to sleep, but as we lent the dog’s owner our instrument, and she was treating the dog carefully with it every day, the dog survived and is alive and kicking now. The list includes a lot of other animals.